|

Printed

from www.digitalmediafx.com

Digital Media FX - The Power of Imagination

Bum Da

Daaa, DaDa Da Dun Daaaa: The Early Animation Composer

by Noell Wolfgram Evans

When Jerry hits Tom over the head with a shovel, the language

of the action is understood across the globe. This is one

of the beauties of animation; it's a translatable art form.

When done properly, a finished animated film can be viewed

and enjoyed (in much the same manner) in countries around

the world. There's only one other medium with such a universal

acceptance rate: music. When Jerry hits Tom over the head with a shovel, the language

of the action is understood across the globe. This is one

of the beauties of animation; it's a translatable art form.

When done properly, a finished animated film can be viewed

and enjoyed (in much the same manner) in countries around

the world. There's only one other medium with such a universal

acceptance rate: music.

Music is

an incredibly expressive medium. In a single note more can

be expressed than what most people express through words in

a single day. That music and animation would join together

is a celebration of common sense. When married properly the

two are a perfect fit, complimenting, driving and inspiring

each other and the audience.

The men

and women who have helped marry music and animation number

in the 100s. From studio composers to arrangers, lyricists

to musicians, each has played an important part in the evolution

of the animated film. Each musician has (or continues) to

offer their own unique outlook to the soundtracks that they

create and yet each also, in some way, builds off of the work

that has proceeded them.

A Quick Start and Stop

While synchronized sound on film had been an experiment for

a number of years, it wasn't until 1927's release of 'The

Jazz Singer' that studios began to see the power of sound.

As that film broke box office record after record, studios

tripped over themselves to get sound films into production.

This of course included all of the cartoon studios. While

Disney is widely credited with having the first sound cartoon

with 'Steamboat Willie' (1928) there were others that came

before him.

The first

animated film with a synchronized soundtrack was actually

completed in 1925 by chronic innovator Max Fleischer. The

short, 'My Old Kentucky Home', made use of Dr. Lee DeForest's

PhonoFilm system. The picture was competent but the system

never caught on with distributors or studios.

The Foundation The Foundation

All good songs come from notes. Many composers create these

notes themselves, but some look to other sources for 'inspiration'.

Raymond Scott was one of these inspirations. Scott was born

Harry Warnow in 1908 (he would change his name several years

later). He started playing the piano at age two and played

around for a number of years before finally getting serious

in 1931 as he was hired to be the staff pianist for the CBS

radio house band. He not only played, but he also began composing

work for the orchestra.

Scott was

truly a unique individual; he had a playful, surreal outlook

on life that he expressed in a particular way through his

music. In 1936 Scott, in an effort to experiment more with

his own compositions, approached CBS about letting him form

a band as a 'side' project. CBS eventually agreed and so 'The

Raymond Scott Quintet' was formed. The uniqueness of the arrangements

and the musicianship of the players led the Quintet to great

popularity. They played on a number of radio programs, toured

the country and even appeared in several movies and yet their

greatest and most lasting success would come from a place

they never suspected: animated films.

A Sample

of Raymond Scott's Songs:

'Dinner Music for a Pack of Hungry Cannibals'

'Powerhouse'

'War Dance for Wooden Indians'

'Careful Conversation at a Diplomatic Function'

Music in Animation Arrives Music in Animation Arrives

Carl Stalling learned the business

of film music from the ground up. He worked during the silent

era as orchestra conductor and composer at the Isis Theater

in Kansas City. His time here was well spent as it gave him

a first hand opportunity to see how audiences reacted to a

musical score, to discover what types of musical ideas worked

with what types of pictures and to see how an audience could

be manipulated through music.

Stalling

was enthralled with the world of film and thankfully for him

so was all of Kansas City. The town was practically over-run

with fledging filmmakers, many of whom spent time in the Isis

and came to know Stalling well. One of the men who became

particularly close to Stalling was Walt Disney.

By the late

1920's, Stalling had moved to Hollywood to stake out a career.

He started to pick up a number of odd jobs and sensing that

things there were only going to get better and better, began

persuading his Kansas City friends to 'head West'. Walt Disney

heard the call and with help from Stalling in the form of

a small loan, he moved his fledgling animation studio to the

California. Stalling became Disney's studio composer and was

responsible for the music in all of Disney's early cartoons,

including 'Steamboat Willie' (1928). Stalling enjoyed composing

for these cartoons but felt that his music was too often being

used either as a novelty or an after-thought. It was out of

Stalling's concerns and desires to see musical scores evolve

that Disney started the Silly Symphony series, the lead cartoon

in which was 'The Skeleton Dance' (1929). This was the first

time in which the action of the animated film was created

around the music. Its phenomenal popular and critical success

helped to bring to a new level of importance to the way music

was viewed in animation. Music was now deemed so important

to animation that musicians and artists at Disney all worked

in the same room.

Stalling

eventually left Disney and worked for several other studios

(including Iwerks) before finding himself at Warner Brothers

in 1936. He remained here until 1958 composing the music for

over 600 cartoons.

At Warner

Brothers, there had always been a caveat attached to the cartoons,

and that was that each should contain a Warner Brothers song.

The advertising and marketing benefits of placing popular

songs in the cartoons was to good for the studio to pass up.

This practice produced such 'classics' as 'Shuffle Off to

Buffalo' (1933). When Stalling arrived at Warner Brothers

the importance of song placement was starting to lag but as

Stalling considered it he realized the brilliance that it

contained. By using popular songs one could easily tie into

the audience's emotions and help direct them down any chosen

path, which in some ways was predetermined by the previously

heard song. Stalling felt the trick though was not to make

a blatant use of a song but rather to incorporate it into

the soundtrack. Take the song 'I'm Looking Over a Four Leaf

Clover'. Previously this song would be given to Porky Pig

to sing as he walked across a farm its presence was pure advertising,

doing nothing to further the action of the film. Stalling

though placed it in a Coyote/Road Runner film as the Coyote

chased the Road Runner around a highway cloverleaf. Its placement

was simple, subtle and incredibly effective.

This is

part of Stalling's genius for he wouldn't just throw a song

into a soundtrack, rather he would take snippets from a song

and thread it in or re-work them until they flowed with the

music and added a punch to the music and action. Stalling's

work benefited from having the large and diverse Warner's

musical catalogue to work with. A catalogue that grew in1943

when Warners bought Raymond Scott Publishing. Stalling now

had a license to use Scott's work. And use it he did.

The Raymond

Scott Archive estimates that Stalling used Scott's music a

total of 133 times in 117 separate cartoons. Far and away

the song used the most was 'Powerhouse'. Its straight ahead

drive instantly puts into your mind an image of Daffy Duck

and Porky Pig working the assembly line in 'Baby Bottleneck'

(1946) (or any number of similar situations). Carl Stalling

had most certainly been providing impressive musical scores

up to 1943 but once he began to incorporate Scott's structured

lunacy into his work, it became inspired and a mark against

which others continue to be measured.

These Stalling/Scott scores were (and continue to be) an inspiration

for established composers and those looking to join the field.

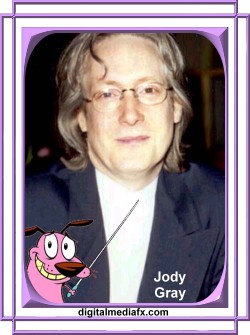

Jody Gray, a composer, says that these scores were 'enthralling'

to him as a child and cites them as a major influence on his

decision to become a composer. Their influence is still felt

at Warner Brothers as well. Gray, who completes a number of

scores for Warner Brother's On-Line animated ventures says

that in discussions, 'Stalling-like' is a description that

is continually bantered about. These Stalling/Scott scores were (and continue to be) an inspiration

for established composers and those looking to join the field.

Jody Gray, a composer, says that these scores were 'enthralling'

to him as a child and cites them as a major influence on his

decision to become a composer. Their influence is still felt

at Warner Brothers as well. Gray, who completes a number of

scores for Warner Brother's On-Line animated ventures says

that in discussions, 'Stalling-like' is a description that

is continually bantered about.

Over at

MGM Scott Bradley had a both enviable and unenviable task:

compose music for the animated shorts being produced there.

This was enviable because of the popularity, both commercial

and critical, of the MGM cartoon stars. Unenviable because

after all, Tom and Jerry films are chase films. Perhaps each

has a different setting, but at their core…. Bradley saw this

challenge and rather than 'cartoon up' his work he took a

more serious approach. An orchestra composer by day, Bradley

used much of the same orchestral overtones in his music for

MGM which provided a certain serious, cynical counterpoint

to all of the action on the screen.

Back over

at Disney, Bert Lewis had taken over for Stalling as Musical

Director and now gave way to Leigh Harline. Harline was the

first college educated Musical Director Disney had; previous

directors had learned their trade in music halls and theater

orchestra pits. The schooling that Harline received paid off

in droves for Disney as he brought a sophistication and complexity

to his scores. Films such as 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'

(1937) and 'Pinocchio' (1940) benefited from his talents.

Many composers of the time composed almost on a shot by shot

basis, but Harline had an ability to compose long musical

themes that would carry out over an entire scene. Within each

musical strand, he would place individual call outs which

could punctuate the action without detracting from the overall

musical 'scheme'.

In Everyone a Song

Stalling, Harline, Scott and Bradley are some of the more influential

composers to come out of the early years of animation but

they are in no way the only composers you have heard. Over

the years we've also been treated to the work of:

Clarence

Wheeler - He worked for Walter Lantz, particularly on

the Chilly Willy series.

Winston

Sharples - Winston wrote music for a number of Paramount

cartoons as well as Merrie Melodie shorts. He would compose

music for 696 animated shorts in all.

Sammy

Lerner - Musical Director at Paramount. His major contribution

was in writing Popeye's theme song.

Sammy

Timberg - The third major Music Director at Paramount.

He was responsible for scoring the majority of cartoons released

between 1942 and 1949.

Ralph

Rainger and Victor Young - Both did work for the Fleischers,

particularly on the feature 'Gulliver's Travels' (1939).

Some studios

left music composition to one person or to a core group while

others worked with music differently on every picture they

created. For example, UPA had no composer on staff. Instead

it kept to its artistic ideals by hiring in a composer for

each particular animated piece. That meant that they could

marry the overall tone of the work with a composer's specific

skills. This put the studio in a partnership with various

talents such as Pulitzer Prize winner Gail Kubik (who scored

the Oscar winning 'Gerald McBoing Boing') and jazz artist

Shorty Rogers (who scored a number of Mister Magoo cartoons.)

As animation

continued to branch out and grow, new composers entered the

field and started to leave their mark. Composers such as:

Hoyt

Curtain - A composer with Hanna/Barbera, he was responsible

for the creation of a number of themes including: 'The Flintstones',

'The Jetsons' and 'Scooby Doo, Where are You?'.

Maury

Laws - The man behind the music of Rankin/Bass.

Howard

Ashman and Alan Menken - They helped Disney achieve new

highs with their work on 'The Little Mermaid' (1989), 'Beauty

and the Beast' (1991) and 'Aladdin' (1992).

Richard

Stone - The Music Director for 'Ren and Stimpy', he brought

Raymond Scotts music back to animation.

Jody

Gray - The composer behind 'Courage, The Cowardly Dog',

Jody is also working on-line, scoring an entirely new generation

of Warner Brother shorts.

Shirley

Walker - Continuing the tradition of amazing musical settings

with her work on 'Spawn' and 'Batman: The Animated Series'.

There are

an incredible number of men and women who have made our cartoon

favorites dance, made them scared, set their moods and given

them music to chase by. As you watch your next animated show,

give yourself an exercise, at some point turn the sound off.

You'll discover that while although the images may still be

incredible to look at, the animation its self is missing something,

it's missing a personality, a tempo, a story spine, it's missing

its music.

--

Noell

Wolfgram Evans is a freelance writer who lives in Columbus,

Ohio. He has written for the Internet, print and had several

plays produced. He enjoys the study of animation and laughs

over cartoons with his wife, daughter, and newborn son. |